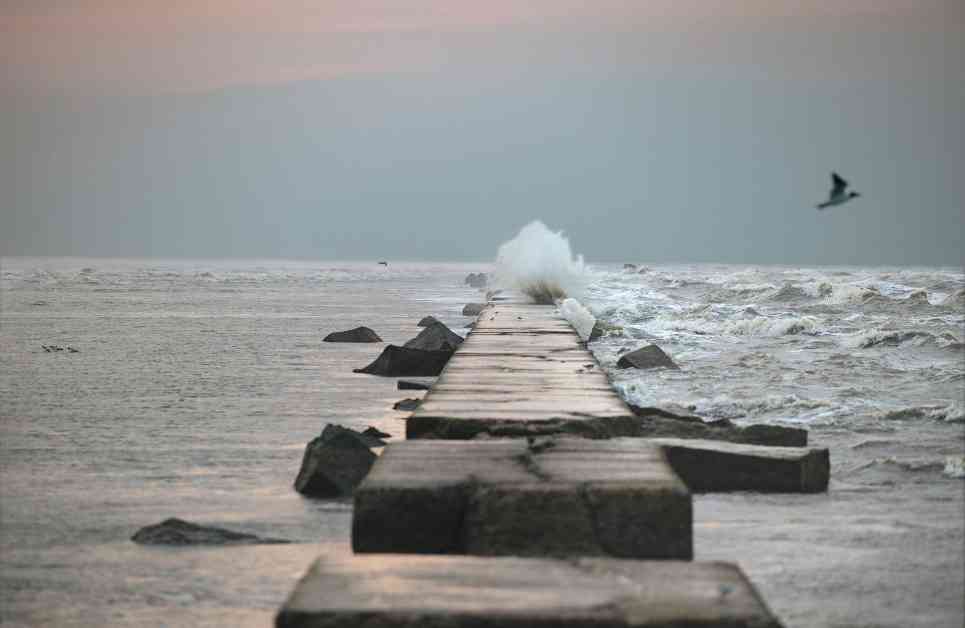

Southeast Texas’ coast is flat and twiggy, bordered mostly by the sea and emblems of the region’s biggest economies—high-rise hotels and oil and smoke-puffing gas refineries. The coastal resort city of Galveston, about an hour’s drive southeast of downtown Houston, transports more tons of cargo than any other port in the United States. It’s a peaceful, watery place. Two long, thin bodies of land stretch toward each other along the Gulf Coast—Galveston Island and Bolivar Peninsula, separated by less than three miles of water at the entrance to Galveston Bay. Each is about 27 miles long and 3 miles wide at its widest point. In between the two is the mouth of the Houston Ship Channel, which provides an estimated $906 billion in economic value to the U.S. each year. Much of that comes from oil and gas entering and leaving the refineries that cluster around Houston.

From the eastern edge of Galveston Island, looking across the bay on an April afternoon, Bolivar Peninsula is barely visible above the sand dunes that line the shore. Cargo tankers stretch far enough to resemble mountains on the watery horizon of the Gulf of Mexico. As tranquil as Galveston may seem, it has been the site of monstrous storms. In September 1900, the Great Galveston Storm flooded the city with a nearly 16-foot storm surge, killing an estimated 8,000 people, to this day the deadliest natural disaster in American history. In September 2008, Hurricane Ike smacked down onto Bolivar Peninsula, destroying 3,600 homes and leaving at least 15 people there dead. More than a million people in the Texas Gulf had to flee, and nearly 2,000 had to be rescued from the storm surge—violent waters thrust up to 20 feet above standard sea levels.

The Army Corps of Engineers started fortifying the city as early as 1914, but sinking ground and larger storms have left the petrochemical corridor open to damage and environmental disasters.

Since then, Texas engineers and lawmakers have been scrambling to find a way to protect the Galveston coastline and the larger Houston region. They’re hardly alone. As climate change brings rising sea levels and as more intense storms batter coastlines, cities along the East Coast, including Miami, Charleston, and the metropolitan centers in New York and New Jersey, are working on plans for expensive coastal-protection projects.

But perhaps no plan is as ambitious—or as ready to go—as the $34 billion project that has emerged in the wake of Hurricane Ike. The coastal Texas project, as it is officially known, draws on techniques pioneered by flood-prone countries like the Netherlands. But it’s been custom-designed for all the different needs of the Galveston coast. Homeowners will be able to look out at sand dunes and restored wetlands, while the city’s business district will be surrounded by reinforced concrete floodwalls. The project’s most ingenious element is a series of 36 sea gates, including two massive gates at the mouth of the Houston Ship Channel, that will seal off Galveston Bay from a devastating surge in the event of an incoming storm. And Texas is due for one. “We have a cycle here of about one every seven years,” says Kelly Burks-Copes, who oversees the coastal Texas project for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. “And it’s been about seven years.”

Burks-Copes, who has a PhD in interdisciplinary ecology and urban-rural planning, and more than a decade of experience on storm-related mega-projects, arrived in Galveston eight years ago. I met her this past spring, when she gave me a tour of the coastline and talked me through the long, complicated journey of the project’s conception and design. With short blond hair and a bright expression, she reminded me of a favorite college professor. “What happened was the storm hit, and a bunch of universities and other entities came up with designs, but nobody could settle on one,” she said. At that point, local Texas governments petitioned Congress to step in, and in 2015 Congress tapped the Army Corps of Engineers to come up with a solution. “We went through all of these plans, and basically drew from them pieces and parts.”

With its patchwork of influences and ideas, the coastal Texas project is unlike anything that has ever been put into practice. Burks-Copes and her colleagues have had to get feedback from a huge cast of characters—petroleum executives and neighborhood environmentalists, ship pilots and academics, federal and state lawmakers. The federal government has promised to pick up 65 percent of the construction costs. Texas will pay for the rest. After a lengthy review process, the final conceptual designs are now set. If the plan succeeds, it could forever change the way Americans mitigate storm damage.