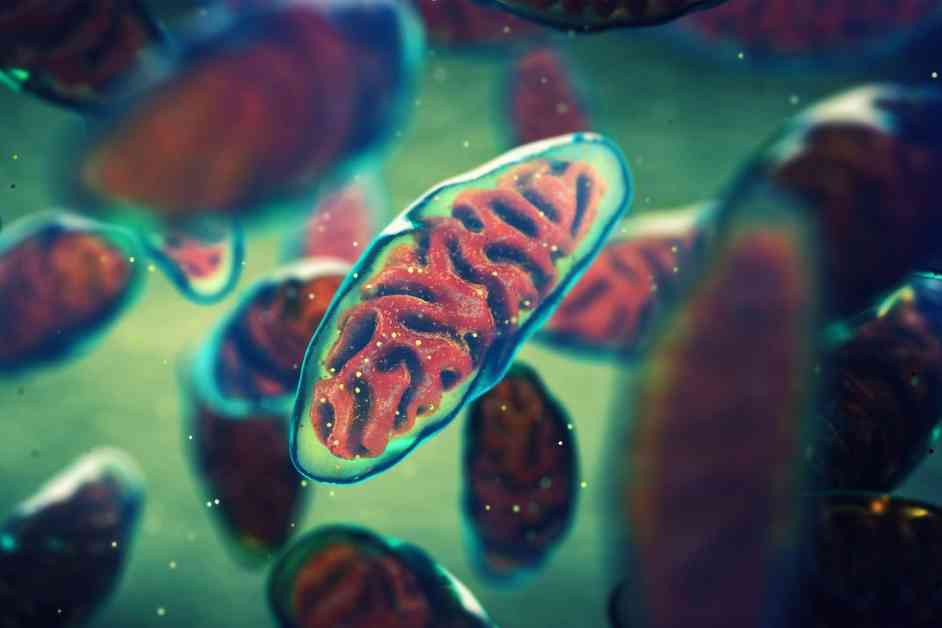

Caroline Trumpff, an assistant professor of medical psychology at Columbia University Irving Medical Center, is delving into the connection between life experiences and brain cell activity. While the link between the mind and body has been established by various studies, applying this knowledge to clinical practice has been challenging. Trumpff’s focus on mitochondria, the tiny structures within cells, aims to shed light on how mental states can impact physical health and vice versa.

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been linked to an array of brain disorders and diseases, including schizophrenia and Parkinson’s disease. Previous research, primarily in animals, has pointed to psychological stress as a significant factor in causing issues with mitochondria. To further explore this relationship, Trumpff and her team analyzed data from the Religious Orders Study (ROS) and the Rush Memory and Aging Project (MAP), which track the health of thousands of older individuals in the U.S. until their passing.

The study specifically looked at how participants’ life experiences influenced the characteristics of mitochondria in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, a brain region involved in emotion regulation and executive functions. Positive experiences correlated with increased abundance of mitochondrial complex I, which plays a role in energy production, while negative experiences were linked to decreased abundance of the same protein complex.

These findings suggest that our life experiences can impact how mitochondria adjust their energy production in response to varying circumstances. Additionally, differences in mitochondrial function could influence mental health and the types of experiences individuals have. Prior studies have shown that chronic stress can alter mitochondria, and mitochondrial defects can impact behavior.

Research outside the brain has also supported these results, indicating that mood and stress levels affect mitochondrial function in immune cells. Mitochondrial dysfunction has been observed in individuals with mental health disorders like depression. These findings underscore the significant influence of psychosocial factors on brain mitochondrial function, which can, in turn, affect cognitive function, psychiatric conditions, and overall well-being.

While the study provides valuable insights, further research is needed to confirm the link between psychosocial factors and mitochondrial function. The study’s focus on older participants raises questions about whether similar relationships exist in younger individuals. Additional studies have shown varying responses of mitochondria to stress and trauma, suggesting that the effects may differ based on the context and duration of stress.

Overall, Trumpff’s study adds to the growing body of evidence highlighting the impact of mental states and life experiences on mitochondrial function. While more research is required to establish causality, the findings present an intriguing avenue for exploration in understanding the intricate relationship between the mind and body at a cellular level.